What are the most common types of medication errors?

The literature suggests that prescribing, administration, and monitoring errors are the most frequent.¹

The literature suggests that prescribing, administration, and monitoring errors are the most frequent.¹

Medicines are the most common therapeutic intervention in healthcare and they have now become much more complex. Although patients benefit considerably as a result of living longer and better quality lives, many experience significant harm due to mistakes or errors in how medicines are used.

What are medication errors?

A medication error is defined as:

Any preventable event that causes or leads to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is under the control of a health professional, patient or consumer.¹

Medication errors occur frequently in health systems around the world, and, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), nearly 50% of preventable harm to patients globally is due to inappropriate use of medicines and other treatments. A quarter of this preventable harm can be severe or even life-threatening.¹,²

Medication errors occur when weak medication systems or human factors affect processes. As a leading cause of avoidable patient harm, a recent study estimated that there are 237 million medication errors in England every year. The majority are thought to have little or no potential for harm but 66 million of these (28%) are potentially significant.³

A European collaboration, European Collaborative Action on Medication Errors and Traceability (ECAMET), aimed at reducing medication errors in hospitals, cited a Spanish study attributing over a third of all adverse events in hospital patients over a five-year period to medication errors.⁴ It is uncertain how many medication errors cause or contribute to patient deaths but a small proportion do have a fatal outcome.

Even when errors are not harmful or severe, they can drive the cost of care up, and the quality of care down.¹ Health professionals do their best to protect patients from harm due to medicines but human factors, such as fatigue and insufficient staffing levels, can play a part. Medication errors that lead to patient harm can negatively impact the mental health of health professionals, and their ability to do their job.⁴

Fortunately, with greater awareness of the scale of the problem, there is now a focus on ensuring a culture of safety in health systems. With the right education, policies, prescribing tools, and reporting and learning systems, errors can be minimised and patients protected.

“Adverse events related to an erroneous use of medication cause greater mortality than traffic accidents, breast cancer, or the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV),” The Urgent Need to Reduce Medication Errors in Hospitals to Prevent Patient and Second Victim Harm, ECAMET, 2022 (ECAMET Alliance, 2022).⁴

What are the most common types of medication errors? The literature suggests that prescribing, administration, and monitoring errors are the most frequent.¹

What are the most common types of medication errors?

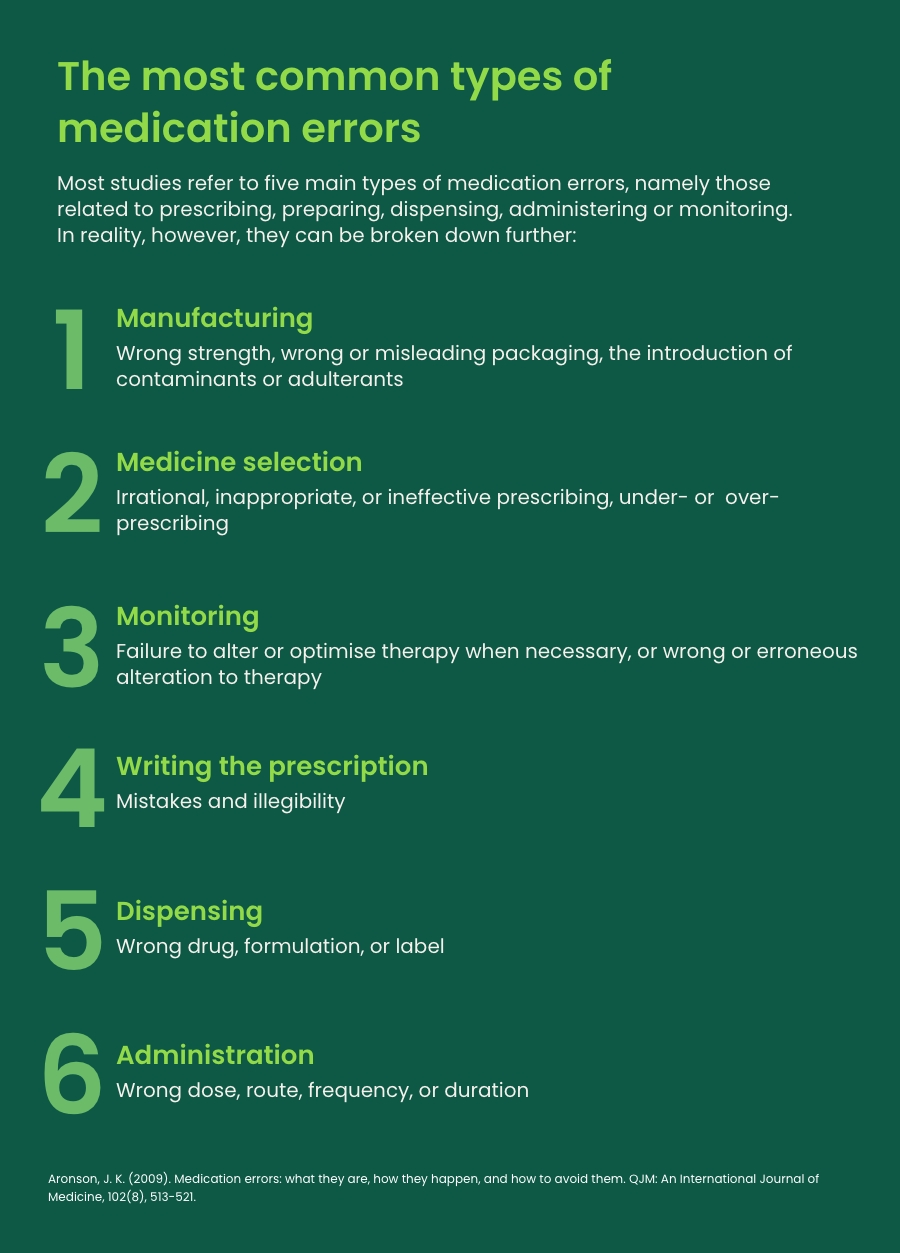

Medication errors can occur at any stage in the medicines use process. Most studies refer to five main types of error, namely those related to prescribing, transcribing, preparation or dispensing, administration, or monitoring. Aronson also noted that errors can occur during the medicine manufacturing process, for example when the packaging is incorrectly labelled or adulterants are introduced.⁵

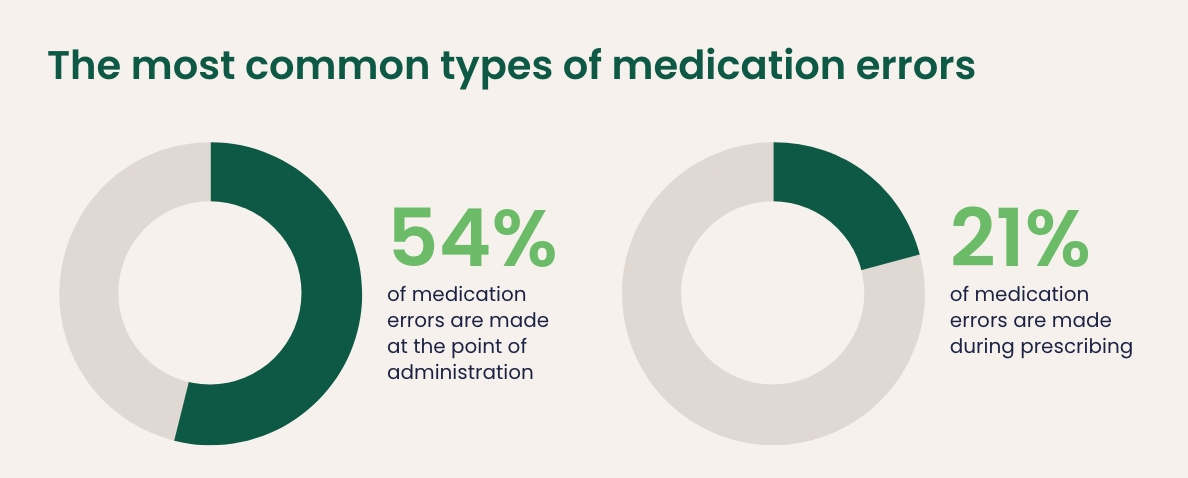

It is challenging to identify and quantify the most common types of medication errors, as research evidence is limited and many go unnoticed or unreported. However, the literature suggests that prescribing, administration, and monitoring errors are the most frequent.¹ The previously mentioned study on the economic burden of medication errors in England suggested that 54% of errors are made at the point of administration, and 21% during prescribing. These figures, the authors explained, are similar to those reported in the USA and European Union countries.³

The most common types of medication errors: 54% of medication errors are made at the point of administration.

Administration errors

Administration errors may include using the incorrect route of administration, giving the drug to the wrong patient, or using the wrong dose or administration rate. The worldwide prevalence of administration errors is around 22%, according to a WHO systematic review.¹

Case study: In 2016 a 50-year-old woman complained of chest tightness, breathing difficulties, and tremors during a colonoscopy at an Egyptian hospital. Health professionals found she had accidentally received adrenaline (epinephrine) instead of midazolam. A root cause analysis found that ampules of adrenaline and midazolam – which were similar in size, shape, and colour – had mistakenly been placed in the same box by pharmacy staff.⁶

NHS Resolution deals with patient claims and complaints in the NHS. Medication errors resulting in claims are likely to represent the tip of the iceberg. Their analysis of medication error claims over a five-year period (April 2015 – March 2020) found that of 487 claims settled with damages paid, 45% related to administration errors. In 27% of these cases, the wrong dose was given, in 18%, the wrong drug was given, and in 15%, the wrong route of administration was used.⁷ The most common medications implicated in these claims were; anticoagulants, antimicrobials, opioids, anticonvulsants, and antidepressants.

Prescribing errors

Prescribing errors account for a high proportion of all medication errors, with the World Health Organization suggesting the error rate may be as high as 53%.¹

These errors can happen at any part of the prescribing process and include irrational, inappropriate or ineffective prescribing, under and over-prescribing, and medicines that are omitted or delayed.⁸

Case study: Anti-infectives (NHS Resolution, 2022, anti-infectives).⁹

NHS Resolution received 172 claims relating to errors with the prescription of antibiotics, antivirals, and antifungals between April 2015 and March 2020.

The key causes of the claims were:

- Failure to check allergy status

- Failure to cross check medication ingredients with allergy status

- Failure to adjust dose to patient weight

- Failure to adjust dose according to patient’s renal function.

The resulting outcomes included anaphylaxis, unnecessary pain, acute kidney injury, and death.

How common are medication errors in primary care?

There is a lack of robust data to quantify the rates of medication errors in any care setting. With primary care generating most NHS prescriptions, however, it is not surprising that most medication errors occur in general practice.³

Research suggests that the error rate in general practice is around 5% of prescriptions, of which 0.18% were severe errors.¹¹

Elliott and colleagues estimated that 34% of all potentially clinically significant errors every year occur in primary care.³ Between 2015 and 2020, NHS Resolution received 112 claims relating to medication errors in general practice. The medications most commonly involved were again anticoagulants, antimicrobials, anticonvulsants, and opioids.

The incidents included well recognised drug interactions, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) being prescribed with anticoagulants despite being contraindicated, due to the risk of adverse gastrointestinal effects.¹⁰ This report also highlighted a case of a prescription for an antimicrobial to a patient with a documented allergy. This resulted in an emergency hospital admission, and a subsequent claim to the state indemnity scheme.

How common are medication errors in secondary care?

Again there is lack of robust data to quantify the rates of medication errors in hospitalised patients.⁵ The prescribing error rate in hospitals is thought to be around 7% of prescription items and the dispensing error rate is thought to be up to 2.7% of dispensed medicines.¹¹

The rate of medicine administration errors is thought to be 3-8%. There is limited research to quantify actual harm arising from medication errors.

High risk situations:

Polypharmacy is known to be an important contributory factor to medication errors.¹ A study in the Netherlands, for example, found that the probability of under prescribing in the elderly increased as the number of prescribed drugs went up. This led to effective treatments for heart conditions and osteoporosis not being initiated.

Medication reviews are a key strategy to reduce harm from errors in patients taking multiple medicines, especially in the elderly.¹,¹² Being familiar with the highest risk medicines is also important.

The medicines commonly associated with preventable errors and patient harm include anticoagulants or antiplatelets, cardiovascular medicines, diuretics, hypoglycaemics, analgesics, antibiotics, and anticonvulsant medicines.¹

The cost of medication errors

While the risk to patients from medication errors must be the key concern, they also have a wider cost or impact, including a detrimental effect on health professionals. ECAMET described the so-called “second victim effect”, that can lead to loss of self-confidence, fear of litigation or reputational damage, as well as guilt and anger.⁴

Furthermore, the WHO noted that an estimated one in 10 nurses with mental and psychosocial health disorders had been involved in an adverse event that had serious consequences for the patient. All of this impacts on people being able to competently perform their duties.¹³

There is also a significant economic cost. Globally, medication errors cost $42 billion a year, accounting for 9% of total avoidable healthcare costs, and 0.7% of all healthcare expenditure.¹ In Europe the annual cost is between €4.5 and €21.8 billion and in the UK alone, avoidable ADRs cost £98.5m a year – or 2.9% of the overall NHS budget.⁴

In Spain the estimated cost of medication errors is €2 billion, around 3% of the country’s total health spend.⁴

Preventing medication errors

Medication errors are a multifaceted problem. Preventable errors can occur for any number of reasons, from illegible prescriptions, incomplete patient records with regard to information on co-prescribed medications, previous response to therapy, and allergy status, to incorrect drug or dose selection and drugs with similar looking or sounding names. With so many contributing factors, there is no one size fits all solution. Rather, tailored approaches to understanding and mitigating the risks are required. Improved systems can help reduce error rates, such as electronic prescribing and automated dispensing.

Reporting all drug errors and near misses, regardless of whether the patient came to harm, and having processes to investigate and analyse the data is crucial. It is only by building the baseline evidence that health systems can better understand how errors occur, and how to prevent them.

“Use of medicines has increased because of increased adherence to disease-based guidance. The increase in use also results, however, in increased hazards, errors, and adverse events associated with medicines, which can be reduced or even prevented by improving the systems and practice of medication,” WHO, Medication Without Harm, 2023.¹

A culture of safety in the health system is necessary to ensure medication safety. With the necessary education, support, and tools, individual health professionals can do much to ensure safe practice.

The “5 Rights” of medication safety can help health professionals who administer drugs to avoid errors.¹⁴

Best practice dictates that nurses and others carry out the following checks before giving a medication:

- Right patient: Check the patient’s name using two identifiers (e.g. wristband, prescription) and the patient to identify themself if he or she is able.

- Right drug: Check the medication label against what has been prescribed.

- Right dose: Confirm the dose using current references, such as local protocols or British National Formulary (BNF). If necessary, recalculate the dose and have a colleague check it.

- Right route: Check the appropriateness of the route that has been prescribed and confirm with the patient if they are able to take the medicine that way. For example, can they swallow a tablet or capsule.

- Right time: Check the frequency of the prescribed medication and confirm when the last dose was given.

Other strategies for avoiding administration errors include:¹⁵

- Following medication reconciliation procedures

- Double or triple checking procedures

- Having a colleague read the prescription back

- Using name alert systems, which alert health professionals to patients with similar names

- Always placing a zero before decimal points to avoid confusion at the point of administration

- Learning the institution’s medication administration policies, regulations, and guidelines

- Documenting the date, time, route, and dosage of the drug.

Both the General Medical Council (GMC, 2021)¹⁶ and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS Competency Framework, 2021)¹⁷ stipulate that health professionals should make use of all available evidence-based resources to keep their knowledge and skills up to date.

In the UK, such resources include those published by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), BNF, and BNF for Children, all of which are essential for practice.

MedicinesComplete

MedicinesComplete brings trusted knowledge products, up-to-date medicines information, and expert guidance on the use and administration of drugs together in one place, helping health professionals to use medicines safely and avoid medication errors.

Discover how MedicinesComplete supports health professionals in confident decision-making at the point of need here.

Please complete the form below to request a complimentary trial to knowledge products through MedicinesComplete.

References

1. WHO. (2023). Medication without harm. Available at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/376212/9789240062764-eng.pdf. Last accessed: 22 April 2024.

2. Panagioti M., Khan K., Keers R.N., Abuzour A., Phipps D., Kontopantelis E., et al. Prevalence, severity, and nature of preventable patient harm across medical care settings: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;366:I4185. doi: 10.11136/bmj.I4185.

3. Elliott R.A., Camacho E., Jankovic D., et al. Economic analysis of the prevalence and clinical and economic burden of medication error in England. BMJ Quality & Safety 2021;30:96-105. Accessed: 1 June 2024.

4. ECAMET Alliance. (2022). The urgent need to reduce medication errors in hospitals to prevent patient and second victim harm. Available at: https://ecamet.eu/wpcontent/uploads/2022/03/ECAMET-White-Paper-Call-to-Action-March-2022-v2.pdf. Last accessed: 16 April 2024.

5. Aronson, J. K. (2009). Medication errors: what they are, how they happen, and how to avoid them. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 102(8), 513-521.

6. Gado, A., Ebeid, B., et al. (2016). Accidental IV administration of epinephrine instead of midazolam at colonoscopy. Alexandria Journal of Medicine, 52(1), 91-93.

7. NHS Resolution. (2022). Did you know? Insights into medication errors. Available at: https://resolution.nhs.uk/resources/did-you-know-insights-into-medication-errors/. Last accessed: 16 April 2024.

8. Cousins D., Crompton A., Gell J. and Hooley J. (2019). The top ten prescribing errors in practice and how to avoid them. Pharmaceutical Journal. Available at: https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/the-top-ten-prescribing-errors-in-practice-and-how-to-avoid-them. Last accessed: 1 June 2024.

9. NHS Resolution. (2022). Did you know? Anti-infective medication errors. Available at: https://resolution.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Did-you-know_-Anti-infectivemedication-errors.pdf. Last accessed: 16 April 2024.

10. NHS Resolution. (2022). Did you know? General practice medication errors. Available at: https://resolution.nhs.uk/resources/general-practice-medicationerrors/#:~:text=NHS%20Resolution%20has%20received%20112,April%202015%20to% 20March%202020. Last accessed: 16 April 2024.

11. MHRA and NHS England. Patient Safety Alert. Stage 3: Directive Improving medication error incident reporting and learning. March 2014. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/psa-sup-info-med-error.pdf. Last accessed: 2 June 2024.

12. Kuijpers, M. A., Van Marum, R. J., et al. (2008). Relationship between polypharmacy and underprescribing. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 65(1), 130-133.

13. WHO. (2022). Key facts about medication errors in the WHO European region. Available at: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/librariesprovider2/country-sites/medication-errorwpsd-final.pdf. Last accessed: 16 April 2024.

14. Hanson, A., & Haddad, L. M. (2022). Nursing rights of medication administration. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

15. Mid Essex Hospital Services NHS Trust. (2018). Medication Error Training Video. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qMuN-MV6Z9Q. Last accessed: 16 May 2024.

16. GMC. (2021). Good practice in prescribing and managing medicines and devices. Available at: https://www.gmc-uk.org/professional-standards/professional-standardsfor-doctors/good-practice-in-prescribing-and-managing-medicines-and-devices. Last accessed: 16 April 2024.

17. RPS. (2021). A competency framework for all prescribers. Available at: https://www.rpharms.com/resources/frameworks/prescribing-competencyframework/competency-framework. Last accessed: 16 April 2024.